Railways were the sole rapid mass transport system that was managed by more than a million people when the Indian subcontinent was partitioned. Syed Shadab Ali Gillani read Aniruddha Bose’s book on the challenges and contributions that the Indian Railways made during the most tumultuous days of its history in the twentieth century starting with the Second World War

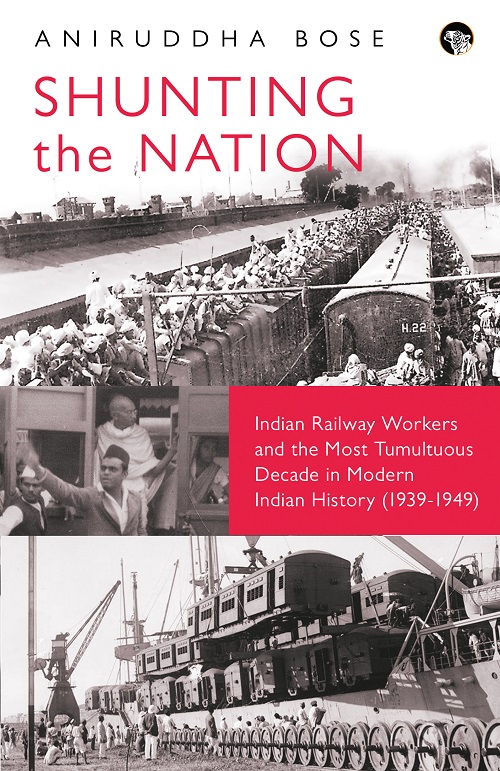

As the subcontinent gave birth to two nations in 1947, the British India Railways had a massive exercise of its history. Aniruddha Bose’s Shunting the Nation: Indian Railway Workers and the Most Tumultuous Decade in Modern Indian History (1939-1949), which Speaking Tiger published recently, provides a fascinating insider’s perspective into the experiences and struggles of the railway workers during the pivotal decade in South Asian history. It relies on a rich array of primary sources to explore how over one million railway labourers navigated immense socio-political challenges and adopted diverse survival strategies as the subcontinent underwent tumultuous transformations.

An Extraordinary Decade

Bose sets the stage by underscoring the Indian subcontinent’s extensive railway network and its indispensable role in transporting freight and passengers. Then, railway workers constituted British India’s largest and most highly diverse workforce, was numbering over one million by the late 1930s.

Bose explains his conceptual focus on survival strategies as an analytical lens for illuminating the experiences of this critical workforce during the tumultuous decade. This period encompassed global World War II, the partition and the making of two neighbour nations. The railway labourers’ roles and responses related to these epic transitions is the book’s core focus. Its structure combines chronological progression through the decade with topical chapters exploring specific subjects.

World War II

The book examines how railway workers mobilised for war, dramatically increasing freight and passenger traffic to meet urgent military needs despite severe equipment shortages. It highlights the tremendous human toll, describing railway workers killed in Japanese bombing raids and the wrenching ethical dilemmas of transporting grain through starving populations during the Bengal famine. Impressive statistics on exponentially intensified workloads convey the herculean efforts of individual railway labourers to support the war effort.

Bose also reveals the extensive wartime militarisation of railway workshops, which produced vast quantities of armaments and munitions. This, he argues, boosted both the wartime economy and workers’ technical skills. However, Bose notes that descriptions of workshop transformations relied heavily on colonial government accounts. Seeking out workers’ voices could provide fuller perspectives on these experiences. Overall, though, the book underscored railway labourers’ indispensable contributions under extreme adversity during the war years.

Freedom Struggle

This chapter explores how railway workers navigated intense political turmoil during the independence movement, facing violent disruptions and attacks even as railway operations remained critical for the colonial regime. Bose documents protesters removing tracks, bombing stations, and assaulting railway guards, while noting many workers’ sympathies with nationalist goals. He argues railway unions treaded cautiously during the Quit India movement, stopping short of endorsing civil disobedience while expressing support for self-rule. This delicate balancing act enabled continued functioning amidst unrest.

According to Bose, the British-controlled Railway Board responded to the Quit India campaign by suspending activist workers and pressing for local assistance in suppressing protests. Yet, nationalist politicians recognised the railways’ importance, urging activists to avoid disrupting essential rail services. The author contends this pragmatic stance on both sides allowed the railway collective to survive the turbulence while furthering the independence movement. However, relying primarily on English-language government accounts may downplay the full extent of railway workers’ resistance and unofficial participation. Consulting vernacular sources could reveal additional insights into the nuances of railway workers’ stances.

Horrors of Partition

Partition, Bose argues constituted the greatest challenge, as escalating communal violence turned the Punjab border into a warzone. Administering the railway split between India and Pakistan brought huge logistical complexities. The workers displayed courage while transporting millions of refugees across hazardous territory. The book cites heart-rending examples of Indian and Pakistani crews striving to mitigate the human tragedy despite horrifying sectarian attacks on trains.

Acknowledging the lack of surviving accounts from workers themselves, Bose skilfully pieces together glimpses into their experiences using English and vernacular newspapers. For instance, he quotes a Pakistani driver’s haunting letter describing fleeing colleagues murdered by rioters. Such fragments help recover perspectives of railway workers facing unimaginable partition violence. By serving selflessly through the suffering, these workers reaffirmed their indispensable role in supporting the vulnerable public and transcending political upheavals. Their efforts epitomised labour’s vital part in national formation.

Class Conflicts

Railway workers also faced entrenched job insecurities, harsh working conditions, and subsistence wages throughout the decade. Bose documents their diverse strategies to press for improvements, including strikes, slowdowns, union organising, and everyday resistance. He highlights the key 1946 rail strike involving over a million workers across India. Settling this strike established constructive labour relations with the interim nationalist government.

Bose contends the positive collaboration following the 1946 strike demonstrated railway unions’ increasing power and set a pattern for constructive labour politics after independence. However, some scholars argue reliance on large organised strikes downplays the persistence of more everyday informal resistance strategies on the railways. Consulting disciplinary records, worker testimonies, or court cases regarding unrest could reveal additional insights into these more subtle survival techniques that likely complement formal protests.

Lasting Legacies

Bose explores the early integrationist efforts and development priorities of the new Indian and Pakistani governments. Despite post-partition disruptions, railway workers played a vital role in rehabilitating refugees, transporting civil servants to new capitals, and distributing essential commodities to prevent famine. Their efforts enabled the fledgling governments to establish authority and embark on reconstruction.

Bose argues this inaugurated a lasting partnership between railway labour and the state centred on shared nation-building objectives. However, evaluating this claim would require examining subsequent labour relations on the railways. Were constructive relationships maintained or did these give way to more antagonism? Consulting records from later strikes, unions, and governments could assess the long-term veracity of this integrationist national partnership.

Strengths

Perhaps the book’s greatest strength is providing a dynamic ground-level view of momentous events through railway workers’ lived experiences. Bose skilfully weaves in gripping first-hand accounts, putting human faces on statistics and epic transitions. We see railway crews improvising to save lives during partition violence, dock workers burying bombing victims, and a young officer disguising a trainee’s religious identity to avoid an attack. Such examples provide invaluable windows into common people’s perspectives and actions as they navigated tumultuous times.

The thematic structure works well, fluidly connecting the chronology across chapters focused on specific topics. Bose effectively balances contextual details and analytical emphasis on survival strategies. Occasional photographs, charts, and maps further illuminate railroad operations. Though not lengthy, the book contains impressive scholarly breadth. During a pivotal decade, Bose explores diverse experiences across railway occupations, communities, and regions.

Limitations

Nevertheless, the book has limitations stemming from its source base and analytical assumptions. Relying heavily on institutional archives and English-language accounts incorporates elite biases. The direct voices of workers themselves are largely filtered through this ruling class prism. Seeking out vernacular sources and worker-authored accounts could reveal more about their outlooks and interpretations. Oral histories with descendants might uncover experiences and stories passed down through railway families. In the Jammu and Kashmir context, the biggest drawback is the author’s failure to document one of the worst communal massacres involving railway passengers.

Similarly, focusing narrowly on organised labour actions overlooks more everyday resistance strategies. Bose touches on tactics like obstruction and theft but these seem secondary. Further exploring more subtle resistance methods would highlight railway workers’ full repertoire of “weapons of the weak.”

Gender and caste also receive inadequate attention. Women workers appear primarily as victims, although they perform vital support roles. Examining their experiences could provide an important gender analysis. Likewise, assessing caste dynamics around recruitment, promotions, and social relations would enrich the account. Integrating intersectional perspectives on how identity-shaped experiences constitute an area for further scholarly investigation.

Conclusion

Notwithstanding the limitations, Bose skilfully utilises the available resources to construct an impressively vivid, nuanced narrative illuminating railway workers’ lives during a dramatic decade. The book represents an important scholarly contribution, deepening the historical understanding of critical labour experiences against the backdrop of pivotal subcontinental transformations.

For labour, partition, and South Asian historians, the extensive original research provides invaluable insights.

Moreover, the personal stories and engaging prose make the book highly accessible to general audiences interested in the human side of epochal events. The rich details and themes could serve as useful teaching material across disciplines encompassing modern South Asia, colonialism, labour studies, and historiography. Aniruddha Bose has produced an exemplary social history repopulating the historical record with subaltern perspectives and underscoring ordinary people’s power to collaboratively determine the course of history even in tumultuous times. Shunting the Nation represents a seminal contribution towards a more inclusive, grassroots-oriented historiography of the subcontinent during a decisive decade marked by both heart-rending tragedy and inspiring determination.